|

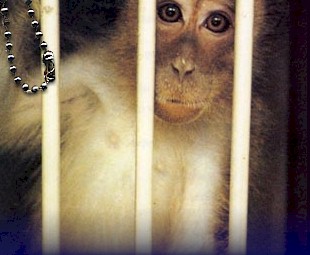

Yerkes worker seems free of infection from monkey BYLINE: Diane Lore and Patricia Guthrie STAFF DATE: 01-01-1998 PUBLICATION: The Atlanta Journal and Constitution EDITION: SECTION: Newspapers_&_Newswires PAGE:A01 Nancy B. Edmunds 41, of Barrow County, was admitted to Emory University Hospital Saturday after being splattered with bodily fluids from a caged monkey she was moving at the lab. She was released Wednesday morning, after tests indicated she did not contract herpes B, a virus common in monkeys but often fatal to humans. Emory officials said she would be returning to work soon. But the incident has intensified an ongoing investigation of Yerkes' safety policies by the Occupational Safety and Health Administration --the federal agency that monitors workplaces for hazards. OSHA already was investigating the death of Yerkes researcher Elizabeth Griffin, 22, who died Dec. 10 after being infected with herpes B by a monkey at the Yerkes field station in Lawrenceville. She also was splashed in the eye with bodily fluids, but did not seek treatment immediately because she didn't regard it as serious. Six weeks later, she died. In the most recent incident, Edmunds was wearing protective goggles --as dictated by new safety policies --but fluid from the monkey seeped in around the sides of the eyewear, according to dmunds' friend Robin Slater. Emory officials said Edmunds has no signs of contracting the virus. "After careful monitoring and testing, her physicians have found no evidence of the herpes B infection," said Emory spokeswoman Sylvia Wrobel in a one-minute-long statement read Wednesday morning on the steps of the hospital. She declined to elaborate or answer reporters' questions. Griffin was wearing standard protective gear at the time of her exposure, but not goggles, because they weren't required for her task of carrying monkeys in fine-mesh cages to their annual physical xams. After Griffin's death, Yerkes officials ordered that protective eyewear be worn for all activities previously considered not risky for herpes B transmission. OSHA, which investigates fatalities in all workplaces, was already inspecting working conditions and interviewing employees at Yerkes because of Griffin's death, but is increasing its scrutiny because of the second incident. Yerkes did not report the latest incident to OSHA officials even though two of its investigators have been examining safety precautions for the past three weeks, said Davis Layne, OSHA's outheast regional administrator. "We found out this through the media coverage and since it seemed so similar to the first case, we decided to look into it," Layne said. "They were not obligated to report this to us. Under the law, an employer only needs to report an employee's fatality or an event that results in the hospitalization of three or more employees." Layne said details were sketchy because many Yerkes employees were off for the holidays. Health officials again cautioned that the public is not at risk for contracting this virus since it does not spread from person to person. ases of herpes B throughout the country typically have involved people who have been bitten or scratched by research or pet macaque monkeys. While 80 percent to 90 percent of macaque monkey have the virus, it only periodically erupts and can then spread, much like herpes simplex in humans. Dr. Jane Koehler, an epidemiologist with the Georgia Division of Public Health, said the state infectious disease office was routinely notified of the exposure but no investigation is planned. Emory officials said the employee would be monitored for "months." But they would not say how or where tests were conducted to etermine that she is probably okay. Upon returning to her home in rural Barrow County near Winder around 4 p.m. Wednesday, Edmunds declined to discuss the matter with a reporter. She also refused comment by phone. Tests for herpes B infection in the United States are performed by the Southwest Foundation for Biomedical Research in San Antonio, which developed a protocol in 1987 that can determine within 48 hours in most cases whether a person is infected, according to the foundation's Dr. Julia K. Hilliard, the nation's foremost herpes B expert. Hilliard is in the process of moving the lab to Georgia State niversity. Between 8,000 and 10,000 such tests are conducted each year, and the research center was consulted on Griffin's case, she said. The center takes swabs and serum samples from both the patient and the monkey and uses a DNA technique known as "polymerase chain reaction" to determine whether the virus is present. It also cultures cells from the exposed site to double-check the results. Culturing cells takes about a week. Once PCR has been done, and no virus found, the patient has a "99.9 percent chance" of not being infected, Hilliard said. However, it s customary for doctors to monitor the patient for about four to eight weeks. There is always a minute chance the virus is merely dormant --which means it could emerge weeks, months or years in the future. "People who have been exposed always have to be on the lookout for symptoms, b ecause there is always that chance the virus is emerging," Hilliard said. The symptoms typically mimic those of a cold or the flu, but quickly become more serious. If there is an indication the virus is emerging, doctors can immediately administer anti-virals --most notably, a drug called anciclovir --that can halt the illness' development, Hilliard said. Because of the test, the fatality rate in humans has dropped dramatically in the past decade. Where humans typically died about 70 percent of the time when infected with Herpes B, now the odds hover at about 50 percent, Hilliard said. Out of the 50 confirmed cases since the 1930s, 26 have been fatal, Hilliard said. |