Monkeys

Monkeys live in nearly every imaginable environment except the arctic. Japanese macaques, or snow monkeys, live in the mountains of Japan and survive cold winters. Squirrel monkeys live in dense tropical forests of South America. Vervets live on the savannas of Africa, and rhesus macaques live commensally with humans in towns and villages throughout India.

World-wide, there are approximately 250 recognized species according to most sources. Occasionally, still, another species is discovered in some remote forest haven. Monkeys live in small groups and large troops. Diets vary from exotic gums and sap to leaves to insects and shellfish to fruits and birds' eggs.

Monkey societies and social interactions have been studied carefully and for extended periods of time. Individuals can be loving, kind, cruel, indifferent, protective, inquisitive, and inventive. They are much like us.

The use of monkeys as research tools in brain science and psychology grew out of our dawning appreciation of the similarity of our minds.

The general scientific recognition of this affinity can be traced back to a common point and place in time.

It was the early 1930s in Madison, Wisconsin, at the Henry Vilas Zoological Park. Abraham Maslow and Harry Harlow began studying monkeys.

Every day, Harry Harlow and Abraham Maslow were a little more impressed by monkeys and what they could do…. It was dawning on them that if one wanted an animal model in psychology, the smart, emotional, complicated monkeys might make a whole lot more sense than the maze-running rats.* (Blum, 2002. p.79.)

Maslow left Madison; Harlow continued to explore the minds of monkeys:

Harlow's work on the process by which monkeys learn to solve discrimination problems began to attract attention. He proposed that monkeys solved discrimination problems by developing “hypotheses” about the situation. According to this view, the process of learning proceeded as incorrect hypotheses steadily were eliminated in favor of the correct approach. These hypotheses could then be applied to similar problems encountered in the future. In his words, the monkeys, “learned how to learn” (Harlow, 149, p.53). This proposal explicitly rejected mechanistic explanations of learning then favored by behaviorists…. Harlow described monkeys as having complex cognitive abilities that involved the existence of intentions, curiosity, and solution plans. This is not a description of insensate automata implied by some behavioristic explanations. (Gluck, 1997, p.149).

Since the early 1930s and 40s, the mental and emotional attributes of monkeys have been of increasing interest to scientists. Many scientists base their use of monkeys on the fact that our fundamental emotions and mental lives are so similar.

The behavioral repertoire of nonhuman primates is highly evolved and includes advanced problem-solving capabilities, complex social relationships, and sensory acuity equal or superior to humans…. Nonhuman primates are capable of advanced behaviors that share important and fundamental parallels with humans. These parallels include highly developed cognitive abilities and binding social relationships. The behavioral repertoire of these animals makes them valuable models for research on the functional effects of exposure to neurotoxic agents. (Burbacher and Grant, 2002. pp. 475-86.)

The evidence of similarity is ever increasing. Papers are published and discussed in the mainstream press with regularity.

These similarities are cause for grave concern. The more like us monkeys are, the more similar are our subjective experiences. The evidence amassed since Harlow's early work demonstrates that empathy for a monkey is not some silly bit of anthropomorphic self-delusion. The evidence is very strong: there is a great likelihood that we share similar subjective experiences.

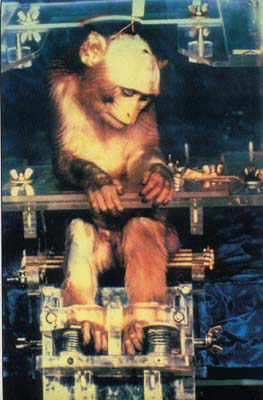

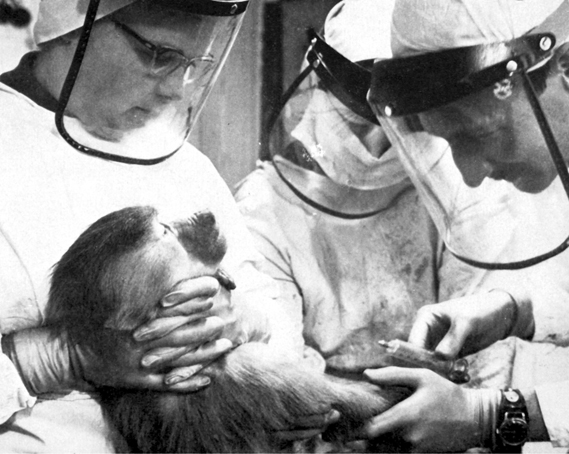

This means that when we imagine what we would be feeling if we were strapped into a chair while someone experimented on us, there is very good reason to believe that a monkey would be having a similar reaction.

This means that the experience we would have if we were caged in a barren cubicle and occasionally grabbed and forced to endure painful and frightening procedures is very likely to be very much the same for a monkey.

The implications are profound. Consider this:

Rhesus monkeys were trained to pull on one of two chains, depending on the color of a flashing light, in order to receive food. After training, another monkey was displayed through a one-way mirror.

By pulling the chains in the correct fashion, the first monkey would receive the food reward, but one of the chains now delivered a powerful and painful electric shock to the floor of the box holding the other monkey. It was discovered that most of the monkeys would not shock another monkey even if it meant not being able to eat. One of the animals went without food for twelve days rather than hurting the other monkey. Monkeys who had been shocked in previous experiments themselves were even less willing to pull the chain and subject others to such torment. (Masserman J, Wechkin S, Terris W. 1964. pp 584-5.)

Today, in the United States alone, between 50,000 and 100,000 monkeys are used in research every year. The details of their use are kept secret. Private industry, such as Covance Laboratories, uses monkeys in toxicity tests. Annually, about 20,000 monkeys are imported and killed in toxicity testing. Little information regarding this private industrial use of monkeys (or any other animals) is available to the public. It is only through the efforts of undercover investigators that we learn what is occurring in these labs.

Publicly funded research using monkeys, like that at the University of Wisconsin, is generally “basic research.”

Basic (aka fundamental or pure) research is driven by a scientist's curiosity or interest in a scientific question. The main motivation is to expand man's knowledge, not to create or invent something. There is no obvious commercial value to the discoveries that result from basic research.

Applied research is designed to solve practical problems of the modern world, rather than to acquire knowledge for knowledge's sake. One might say that the goal of the applied scientist is to improve the human condition. ( Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory )

We can learn bits and pieces about the research going on in labs like the UW's because the research – and the labs themselves – are paid for by taxpayers and subject, to a small degree, to state and federal public records statutes. Additionally, the publish-or-perish world of academia results in papers that occasionally provide a window into these labs.

The gory details regarding the use of monkeys in these taxpayer-supported labs are actively hidden and kept inaccessible to the public by the universities. When details do emerge, they are frantically spun by the public relations departments to confuse and muddy the issue in the public's eyes.

Given what we know about the minds and emotions of monkeys, consider what the monkeys in Dr. Ei Terasawa's seventeen-years-long research project must have experienced during their three- day-long episodes of being strapped into a chair while pumps pushed and pulled chemicals from their brains.

Or, consider the UW's psychiatry department's chair Dr. Ned Kalin's recent publication, “Calling for help is independently modulated by brain systems underlying goal-directed behavior and threat perception.” Kalin et al explain:

This result suggests that the drive for affiliation and the perception of threat determine the intensity of an individual's behavior during separation. These findings in monkeys are relevant to humans and provide a conceptual neural framework to understand individual differences in how primates behave when in need of social support. (Fox, et al. 2005)

It comes down to this: Through the use of scientific methods, careful observation, controlled experimentation, repeated demonstrations, and various manipulations, we have discovered that animals other than ourselves have complex minds with sophisticated mental capabilities like analogical reasoning (Fagot J, Wasserman EA, Young ME. 2001), numerical computation (Sulkowski GM, Hauser MD. 2001), a sense of fairness (de Waal, 2005), tool use (Ducoing AM, Thierry B. 2005), and they possess unique and describable cultures (Sapolsky RM, Share LJ. 2004).

In other words, we have discovered another group of intelligent and emotional beings within our midst. This discovery should give us pause. We cannot rely on the scientists using these animals to make the right moral choices; they have proven that they see these profound similarities as reason to exploit these animals further; as a justification for hurting and killing them. Such a position is clearly immoral or evidence of criminal insanity.

Good people must educate themselves in order to speak knowledgeably about this matter and to advocate for these victims and to demand that we modify our behavior in a way that acknowledges that we are not the sole species on this planet capable of love, hope, fear, or pain.

Monkeys are enough like us that only bigotry, the same sort of prejudice that kept women and people of color subject to the whim of the rulers for so long, explains our current cruel relationship with them. It is time for a more progressive perspective.

*There is good evidence -- and many claims by scientists using them -- that rats do indeed have many mental and emotional similarities to humans. Given the recent development of mammals, in evolutionary time, we should expect many such similarities between us all.

Works cited:

Burbacher TM, Grant KS. 2000. Methods for studying nonhuman primates in neurobehavioral toxicology and teratology. Neurotoxicology and Teratology. Jul-Aug; 22(4): 475-86. Review.

Blum, D. 2002. Love at Goon Park: Harry Harlow and the Science of Affection. Perseus.

Ducoing AM, Thierry B. 2005. Tool-use learning in Tonkean macaques (Macaca tonkeana). Anim Cogn. Apr;8(2):103-13. Epub 2004 Sep 22.

Fagot J, Wasserman EA, Young ME. 2001. Discriminating the relation between relations: the role of entropy in abstract conceptualization by baboons (Papio papio) and humans (Homo sapiens). J Exp Psychol Anim Behav Process. Oct;27(4):316-28.

Gluck JP. 1997. Harry F. Harlow and animal research: reflection on the ethical paradox. Ethics Behav. 7(2):149-61.

Harlow HF. 1949. The formation of learning sets. Psychological Review. 56, 51-65 (Quoted in Gluck, 1997.)

Sapolsky RM, Share LJ. 2004. A pacific culture among wild baboons: its emergence and transmission. PLoS Biol. Apr;2(4):E106. Epub 2004 Apr 13.

Sulkowski GM, Hauser MD. 2001. Can rhesus monkeys spontaneously subtract? Cognition. May;79(3):239-62.

de Waal FB. 2005. How animals do business. Sci Am. Apr;292(4):54-61.

[Expert opinion concening the similarity between us monkeys:

Monkey Mind.]

Madison's Hidden Monkeys is a joint project of the

Alliance for Animals and the

Primate Freedom Project