Who is Seymour Levine?

Fall, 2000

Levine has just published his

newest paper on the minutia of neurochemical imbalance induced

through early social disruptions and/or maternal stress in

squirrel monkeys.

In this paper, Influence of psychological variables on the

activity of the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis (European

Journal of Pharmacology, 2000, September 29), Levine continues

to document the long-term, sometimes life-long, metabolic

vulnerability of infants who experience early emotional distress.

Levine writes, "The interaction of the developing rodent

or primate with their primary care giver has permanent long-term

effects on the HPA axis. Manipulations that alter maternal

behavior during critical periods of development permanently

modify the HPA axis. The HPA axis can be programmed to be

hypo-responsive or hyper-responsive as a function of time

and length of maternal separation. In the adult organism,

the HPA response to stress is highly dependent on specific

psychological factors such as control, predictability, and

feedback. In primates, social variables have been shown to

diminish or exacerbate the HPA stress response."

A sampling of Levine's publishing history shows that he has

spent a lifetime hurting baby animals and cashing in on the

public's confused notion of research and our gullible belief

that important knowledge always results from any macabre sacrifice

of animals. In Levine's defense it must be noted that much

of society holds the baseless belief that all scientific experimentation

is good, ethical, productive scientific research. Some portion

of this confused public is likely to, themselves, become practitioners

of this system; they believe in it. We must pray, in order

to maintain respect or hope for our culture and species, that

Levine is a victim of the system that validates and rewards

repetitive and meaningless cruelty when it poses in white

coats.

But Levine is guilty of a pedantic faith in the value of

his research; a position that flies in the face of the scientific

method, and one that would be scorned in most branches of

real, as opposed to pseudo-science. Levine was interviewed

by the Pulitzer prize winning news writer, Deborah Blum, in

preparation for her award winning Monkey Wars. The

interview, in the Fall 1992 Research Reporter (Vol. 22 No.2)

is illustrative of the mindset of primate vivisectors in general.

Blum wrote: "A few scientists were almost astonishingly

open . . . Seymour Levine, a Stanford University biologist

and a favorite target of the animal rights movement, was equally

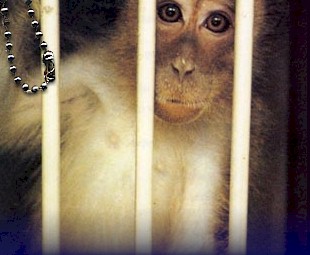

prompt in agreeing to talk. Levine works in the controversial

area of maternal deprivation, separating infant monkeys from

their mothers. He has been picketed, leafleted and hung in

effigy for almost a decade. But he spent hours with me, talking

about his work, taking me to see his squirrel monkeys, determined,

he said, not to let anyone devalue his studies."

But the "devaluation" of Levine's studies is shown

by the absence of benefit to others stemming from his life's

work. Levine is cited commonly in studies that repeat the

demonstration that animals can be permanently damaged when

distressed at an early age, but the frequency of such citations

falls precipitously in literature dealing with human children.

By 1968, Levine had risen to the top of the "psychobiology

of development" food chain. The psychobiology of development,

as an animal-based research endeavor, often focuses on the

long-term results of harming infants. Levine co-edited the

extensive text, Early Experience and Behavior, in 1968.

(Levine and Newton, Thomas Books, Springfield, Illinois. 18

chapters, multiple contributors, 718 pages).

Levine's early work focused on harming rat pups in various

ways and then documenting the psychobiological effects of

that harm. Writing in Early Experience and Behavior,

Levine explained a component of his work at that time, "At

forty-six days of age, half of the rats in each group received

electroconvulsive shock. Twenty-four hours later, blood samples

were obtained from all animals and glucose concentration was

measured," ("Hormones in Infancy," in Early

Experience and Behavior, page 174).

He began "Hormones in Infancy" with the explanation

of work he had conducted in 1956, "Early research (Levine

et al., 1956) on infantile experience dealt with rats treated

in infancy either by simply picking them up once daily and

placing them in a different environment for three minutes,

or by giving them three minutes of electric shock daily until

they were weaned at twenty-one days." ("Hormones

in Infancy," in Early Experience and Behavior,

page 168).

In 1978 he published "Prolonged cortisol elevation

in the infant squirrel monkey after reunion with mother."

(Physiology and Behavior, 1978, Jan) which he co-authored

with Chris Coe, now director of the infamous Harlow Primate

Psychology Lab in Madison, Wisconsin. Levine has been a frequent

collaborator of Coe's.

A short list of papers Levine either authored or co-authored

serve as mile posts along a wasted career:

· Mother-infant attachment in the squirrel monkey:

adrenal response to separation. (Behavioral Biology, 1978,

Feb)

· Separation distress and attachment in surrogate-reared

squirrel monkeys. (Physiology and Behavior, 1979, Dec)

· Behavioral and pituitary--adrenal responses during

a prolonged separation period in infant rhesus macaques. (Psychoneuroendocrinology,

1981)

· Hormonal responses accompanying fear and agitation

in the squirrel monkey. (Physiology and Behavior, 1982, Dec)

· Social and environmental factors influencing mother-infant

separation-reunion in squirrel monkeys. (Physiology and Behavior,

1985, Apr)

· Effect of maternal separation on the complement

system and antibody responses in infant primates. (International

Journal of Neuroscience, 1988 Jun)

· Behavioral and physiological responses to maternal

separation in squirrel monkeys (Saimiri sciureus). (Behavior

and Neuroscience, 1990, Feb)

· Behavioral and physiological responses of mother

and infant squirrel monkeys to fearful stimuli. (Developmental

Psychobiology, 1992, Mar)

· Early experience effects on the development of fear

in the squirrel monkey. (Behavioral and Neural Biology, 1993,

Nov)

· Separation induced changes in squirrel monkey hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal

physiology resemble aspects of hypercortisolism in humans.

(Psychoneuroendocrinology, 1999, Feb)

|