|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Why Animal

Experimentation Matters This review takes its name from the title of a collection of essays

published in 2001: Why Animal Experimentation Matters: The Use

of Animals in Medical Research (Ellen Frankel Paul and Jeffrey

Paul, editors; published by the Social Philosophy and Policy Foundation

and by Transaction Publishers. Paperback edition.) Why Animal Experimentation Matters: The Use of Animals in Medical

Research includes three essays from scientists who experiment

on animals and six essays, including the introduction, from philosophers

who defend animal experimentation and other uses of animals as well.

The essays present various justifications for using animals in medical

research, product testing, and even recreational killing (i.e. bullfights,

etc.). Discussions includes the moral value assigned to pain and

suffering in humans and nonhuman animals, the moral value assigned

to human and nonhuman lives, and the moral value assigned to human

and nonhuman actions. All of the essayists begin with the assumption that the current

use of animals by humans is as it should be, or is overly regulated

and constrained. In various ways, they all try to justify human

domination over all other species. They do not agree as to why humans

have a right to exploit animals, but they do agree that this is

a right that humans possess. Philosophical positions can be evaluated only by their results.

In other words, if one develops a seemingly rational and self-consistent

philosophy that results in a justification of widespread, institutionalized,

industrialized, routine evil, then the premises on which the philosophy

is based, or the arguments stemming from the premises, must be flawed. As in mathematics, claimed solutions to philosophical problems

must be checked. Consider the elementary logic problem of the traveler

with a hen, a fox, and a bag of corn who tries to cross a river

in a boat large enough to carry only herself and one of her possessions.

A problem arises if she carries the corn across first. While she

is gone, the fox will eat the chicken. If she carries the fox across

first, then the chicken will eat the corn while she is in the boat

with the fox. A similar problem occurs as hen, fox, and corn arrive

and are left alone on the other side of the river. The goal is to get the traveler, the corn, the hen, and the fox

across the river safely. Solutions that fail to meet this requirement

are incorrect. No degree of narrative, explanation, or justification

will suffice to overcome this requirement. Discussions about the

relative worth of the corn, the hen, and the fox may be able to

contrive speculative value-laden hierarchies and explain why it

would be justifiable to sacrifice the fox, the hen, or the corn,

but they would be incorrect solutions to the problem. The use of animals in medical research is generally accepted to

be a problem. Proffered solutions have been varied. The federal

government’s solution to the problem has been regulation.

Solutions offered by the essays in Why Animal Experimentation

Matters: The Use of Animals in Medical Research generally rest

on speculative value-laden hierarchies or a denial that a problem

exists. Like the fox, hen, and corn problem, it should be possible

to check a proposed solution to the problem if we knew what condition

a solution should produce. In the case of the fox, hen, and corn,

a correct solution will get the traveler and her possessions safely

across the river. The solution to the problem of harming animals in medical research

would include not harming them, no animals kept in labs, and continued

progress in health care. The current situation demonstrates that a solution to the problem

has yet to be put into practice. The current solution, that offered

by the regulatory effort of the federal government, has resulted

in an industry that is responsible for widespread, institutionalized,

industrialized, routine evil. How widespread is the problem? Federal regulations require that many products be tested on animals

prior to being tested on humans or marketed for human use. All new

drugs, all new food additives, and many household and commercial

chemicals are applied to, force fed, or injected into animals. A

single commercial testing laboratory can use five hundred animals

a day. Every major university in the country and many smaller universities

and colleges receive funding from the federal government to engage

in animal experimentation. For many schools, this funding has become

a major source of income and an economic resource they defend vigorously. Schools, from elementary to high school, dissect animals and use

them in science classes in various ways including demonstration

and experimentation. It is unlikely that anyone living in the United States is more

than a short distance from a facility that is related in some way

to the consumption of animals for experimental purposes. In what sense is the problem institutionalized? The vivisection industry is promoted through direct federal support

as mentioned above, but the industry has also become an institution

within the government itself. The National Institutes of Health

(NIH) is comprised of many scientific bodies such as the National

Cancer Institute (NCI), the National Institute of Drug Abuse (NIDA),

the National Institute of Child Health and Human Development (NICHD),

and the National Institute of Mental Health (NIMH). All of the bodies

fund vivisection directly through grants to researchers, private

companies, and public institutions. The National Center for Research

Resources (NCRR), yet another of the 27 Institutes and Centers called,

collectively, the NIH, is dedicated to providing resources to the

vivisection industry. NCRR funds the breeding of mice, rats, primates,

invertebrates, and supports the infrastructure needed to accomplish

this task. Recently, NIH announced a name change for its eight flagship Regional

Primate Research Centers. They are now billed as National Primate

Research Centers. Though the Department of Health and Human Service’s NIH

is the best-known example of federal institutionalization and bureaucratization

of the vivisection industry, it is not unique. The Department of

Agriculture (USDA), the Department of Defense (DOD), and the Department

of Veterans’ Affairs (VA) all maintain large industrialized

facilities dedicated to breeding and experimenting on animals. Most

cabinet level agencies are involved in vivisection to some degree. How industrialized is vivisection? The precise number of animals consumed in scientific use in the

U.S. is unknown. No reliable data exists on which to base an estimate,

but bits and pieces can be analyzed. The United States Department

of Agriculture (USDA) requires animal laboratories to report the

number of certain animals they use each year. These reports include

the number of dogs, cats, primates, hamsters, guinea pigs, rabbits,

“farm” animals, and “other” animals.

“Other” animals include all other mammals except purpose

bred mice and rats. The USDA does not count purpose-bred mice or rats. Neither does

it count birds, fish, reptiles, amphibians, or invertebrates. According

to a survey conducted by the National Association for Biomedical

Research, 17 million mice were used in 1998. The number was expected

to increase by 50% within five years. The 17 million mice used in

1998 represent a small percentage of the mice killed to support

the demand for them. The escalating demand is due to the industry’s

ability to produce mutants with known genetic profiles. The Mouse Genetics Core (MGC) provides “a cost-effective

method for generating and maintaining transgenic and chimeric mice

for the Research Community at Washington University.” MGC

explains what it takes to produce mutant mice: In the case of transgenic mice, for each two to eight animals sent

on to a scientist to experiment on, twenty to fifty mice must be

produced and screened. Those not meeting the genetic criteria are

killed. For chimeric mice, for each two to six that are sent on

to a scientist to experiment on, twenty to forty will be born and

tested. Thus, in the best-case scenario, eight out of twenty animals born

go on to be used. This means that the 1.7 million mutant mice produced

and sold by NIH-commissioned Jackson Laboratory in 1997 actually

represent between 4.25 million and 85 million animals. Production

of such a large number of animals requires much mechanization. Laboratory

supply catalogs and journals increasing tout entirely automated

robotic systems. The total number of rats used annually is estimated by the industry

to about a third to a quarter of the number of mice actually used.

No estimate for the number of other unregulated animals is available,

but it must be immense. Production of many of these animals, especially

the smaller species such fruit flies and worms, is highly mechanized.

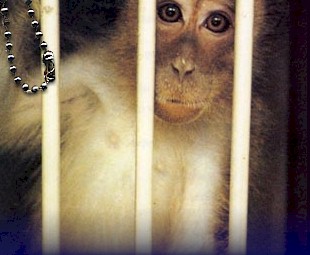

Animal production facilities have become animal factories. Though far fewer primates are used than mice, the large primate

production and vivisection facilities are now inspected and judged

according to industry standards. The injections and blood draws

of thousands of animals daily has necessitated a factory-like ability

to manipulate animals on an assembly-line basis. In what ways has evil become routine? Here, evil is defined as the causing of injury, pain, or misery.

The infliction of injury is essentially synonymous with vivisection.

Essentially all laboratory research using animals inflicts injury.

These injuries come in many varieties. Many animal models of human

disease are based on the chemical or surgical creation of infirmities.

Other models are based on the infection of animals with diseases

claimed to resemble human diseases. Other models are based on illnesses

caused by inadequate nutrition. Other models are based on the psychological

wounding of animals through unnatural rearing conditions. Animal

models are created by addicting animals to narcotics or through

chronic infusions of drugs, hormones, or other chemicals. Some animals

are used to judge the toxicity of a chemical by determining the

amount needed to kill the animal. Here are few, if any, animal models

that do not entail the infliction of injury in some form. Pain is acknowledged by the industry to be difficult to gauge in

an animal. As a result, the degree of pain experienced by animals

as a result of the U.S. vivisection industry’s activities

is under-reported. Under-reporting of pain is beneficial to the

institution and to the scientists, as doing so reduces their paper

work burden. Scientists using covered species are required to explain

ahead of time how they propose to mitigate the pain they plan to,

or inadvertently will, cause. Researchers in non-registered laboratories,

using non-covered species, are not required to do this. Research

on pain begins with the object of causing pain in the animals being

studied. Misery in animal laboratories is ubiquitous. Stereotypical behavior

in animals held in labs is a common topic during laboratory animal

conferences. Such lab-induced behaviors include over-grooming, odd

postures, odd movements, and self-mutilation. Over-grooming can

result in nearly complete hair or feather loss. Odd postures can

include chronic shaking, chronic submissive or aggressive postures,

or standing in a particular spot for hours on end. Odd movements

can include endless pacing, spinning, looping, side-to-side swaying,

head shaking, and combinations of such behaviors. Self-mutilation

is more common in primates than other species. The industry estimates

that 10% of the monkeys in U.S. labs mutilate themselves to such

a degree that veterinary intervention is required. Such mutilations

include gnawing fingertips, arms, and tail to such a degree that

chronic wounds result. Chronic diarrhea of no known cause is chronic

in U.S. monkey labs. The industry acknowledges the evil inherent in animal experimentation.

It is common to hear this acknowledgement in the statement that

animal research is a “necessary evil.” This evil is routine in animal labs. It is the nature of such labs

that evil will be common. The authors of the essays included in Why Animal Experimentation

Matters: The Use of Animals in Medical Research present moral

theories that support and promote this evil. This simple fact exposes

the authors’ philosophies as failed solutions to the problem

of evil inherent in these labs. In the remainder of this essay I

will examine the claims made by these authors and point out where

their moral theories may have gone wrong. I repeat my claim: If

one can develop a seemingly rational and self-consistent philosophy

that results in a justification of widespread, institutionalized,

industrialized, routine evil, then the premises on which the philosophy

is based, or the arguments stemming from the premises, must be flawed.

Let us look for those flaws. “Experimental Animals in Medical History” by Kenneth

F. Kiple and Kriemhild Coneé Ornelas (pg 23-48). Kiple and Ornelas base their support of animal research on two

claims – the first one is questionable and the second, speculative.

Their first claim is that most, if not all, medical progress is

a direct result of animal experimentation. This is an old claim,

made by many defenders of the status quo. The authors cite a litany

of conditions, diseases and knowledge that they imply would have

been impossible to prevent, cure, or gain, without the use of animals.

Their propensity to link all advancements in human knowledge of

biology with the use of animals is explicit early in their essay

when they claim that prehistoric humans must have learned about

basic anatomy while butchering animals. Undoubtedly, humans learned about the appearance, shape, and location

of human organs from seeing them in humans who had been injured,

wounded, or killed. The authors extend their logic to encompass

the claim that every scientist who happened to use animals had to

have used animals in order to have made their discoveries. They

studiously avoid discussion of the pervasive evidence that animal

models have been at least as misleading and deadly as they have

been productive. The second claim on which the authors base their defense of animal

experimentation is that future medical progress will require the

use of animals. They state that animals will be “absolutely

indispensable” for conquering new viruses as they emerge.

They claim that “even hindering” the use of animals

in biomedical or biotechnological research is “suicidal.”

At best, these claim are speculative. At worse, they dismiss the

leading-edge technologies that are proving to be much faster and

reliable tools for the development of drugs and therapies. [For an in-depth examination of both of the claims made by Kiple

and Ornelas, see Jean Swingle Greek and C. Ray Greek, Specious

Science: How Genetics and Evolution Reveal Why Medical Research

on Animals Harms Humans. Continuum Publishing, May 2002. Throughout

the essays in Why Animal Experimentation Matters: The Use of

Animals in Medical Research, the authors claim that animal experimentation

saves human lives. This claim is made repetitively. See Greek and

Greek for a refutation of this myth.] Kiple and Ornelas fail to present much of a moral theory. Their

theory is simple self-interest. The interests of the animals being

consumed by the widespread, institutionalized, industrialized, routine

evil are not addressed. “Making Choices in the Laboratory” by Adrian R.

Morrison (pg 49-77). Adrian Morrison’s moral theory is one of default. He believes

that those who experiment on animals do so with God’s blessing.

Not surprisingly, he feels that those who oppose animal experimentation

are evil. This is rationally unassailable. Once one is convinced

that one stands on the side of God, those who criticize you must

be on the side of evil. Such faith leaves little room for rational thought. Morrison’s

irrationality allows him to claim that he is protecting the weak

and the helpless from those who consider themselves competent to

decide the fate of others. He believes that he knows better than

the evil animal rights activists, presumably because he and the

vivisection industry are on the side of God. Morrison’s essay is generally unremarkable except for the

fact that he himself is a vivisector. He spent years experimenting

on the brains of cats, and says that now he is relieved to be able

to experiment on rats instead. There is one part of his essay that

stands out, and that is his justification, or lack thereof, for

the line of research he chose to make his life’s work. Morrison says that he can imagine nothing worse than to suffer

traumatic brain or spinal chord injury. He uses such injury as the

ultimate example of a need for animal research three times in his

essay. But Morrison’s research area is sleep and wakefulness.

Further, he says that he chose not to perform certain experiments

on his cats because they would have been very painful, but that

in hindsight, he now thinks that those experiments would have been

ethically acceptable after all even though newer methods have made

the methods he would have used obsolete. Morrison’s reliance on a faith that God condones animal

experimentation has resulted in confused and meaningless claims.

His moral theory produces more questions than answers, and he fails

to plumb the depths of his God-created pain- and misery-filled world.

Most importantly, he does not address the motivations of a deity

who would countenance His creation being consumed by the widespread,

institutionalized, industrialized, routine evil called vivisection. “Basic Research, Applied Research, Animal Ethics, and

an Animal Model of Human Amnesia” by Stuart Zola (aka Stuart

Zola-Morgan) (pg 79-92). Stuart Zola presents no moral theory for why animal experimentation

should be condoned. One section of his essay, titled: “The

Moral Issue Regarding Animals” turns out to be only a weak

justification of his own basic research on monkeys’ brains. Zola’s justification for his experiments comes down to the

claim that knowledge alone is an adequate reason to harm animals.

His experiments fall within the general category of “basic

research.” That is, he is not trying to cure a disease, he

is not trying to develop a new treatment, and he is not trying to

alleviate suffering. He is simply trying to determine how to induce

amnesia in monkeys through brain injury. Zola has demonstrated that

the greater the area of a monkey’s brain that is damaged,

the greater is his or her memory deficit. Zola’s proffered justification has three parts: 1. Experiments

should be allowed if they utilize “good science.”

2. New knowledge is just cause to experiment on animals. 3. There

is no way to tell in advance whether something discovered might

someday, somehow, be of some benefit to someone. Zola sums up his position this way: “Therefore, it might

not be reasonable to preclude the possibility of carrying out a

study simply because it has no obvious immediate relevance, either

potential or real.” He repeats this assertion on three separate

occasions in his short essay. In answer to those who have presented cogent theories explaining

why animals should not be harmed in biomedical research, Zola says:

“For some individuals, animal research is simply not a debatable

topic. From their perspective, animals should not be used in biomedical

research under any circumstances. There is presumably no argument

or discussion that could alter this viewpoint, and this viewpoint

will not be considered further here.” Zola’s position

of authority suggests that presumptions of correctness and dismissals

of cogent argument contrary to beliefs held by him and his peers

are devices that protect some within the vivisection industry from

meaningful self-reflection. His unwillingness to think may be based

on an awareness of where thoughtful and careful analysis will lead. Stuart Zola is the current director of the NIH Yerkes National

Primate Research Center at Emory University in Atlanta. He is responsible

for much that occurs there. Yerkes is a well-known cog in the widespread,

institutionalized, industrialized, routine evil of animal experimentation.

His assertion that animal experimentation requires only the weak

justification of providing new knowledge is a clear statement about

the true nature of the industry’s concern for those they

vivisect. Zola’s errors are rooted in the fact that he confuses his

wish to learn about the workings of monkeys’ brains with

the right to do so. Zola has renamed Morrison’s God, Knowledge. “The Paradigm Shift toward Animal Happiness: What It

Is, Why It Is Happening, and What It Portends for Medical Research”

by Jerrold Tannenbaum (pg 93-130).

Jerrold Tannenbaum writes about his concern for what he perceives

to be a shifting of the traditional paradigm concerning human uses

of other animals. He says that in the “traditional approach”

that “there is no ethical import in killing animals per se,”

[his emphasis.] He says that: “Our primary ethical obligation

when we use animals (in research or agriculture, for example) is

to avoid causing them ‘pain’ or more ‘pain’

than is necessary or justifiable.” He defines ‘pain’

broadly as “unpleasant mental states” such as physical

pain, suffering, stress, distress, and discomfort. Tannenbaum goes on at length to describe the regulations that appear

to assure that the traditional approach is adhered to in laboratories.

He worries though, that effort to assure animals’ welfare

is leading to the belief that the animals have a right to be happy

when they are not being actively used. He says that: “if

research animals come to be viewed as our friends – and as

worthy of happiness and happy lives as we are – animal research

will stop.” His concerns appear to be rooted in a faith that

animal experimentation is the only avenue available for biomedical

research. [Again, see Greek and Greek for a complete refutation

of this myth.] Tannenbaum appears to be lost in an inconsistent worldview, due

at least in part to an ignorance of animals that, ironically, he

feels may be part of the cause of the paradigm shift that he claims

to see. He admits that there are animals (pets) about whom we know

enough to say that they can have happy lives and enjoyments. He

also admits that it may be ethically obligatory for us to seek their

happiness. But he claims that it is not irrational to care deeply

about some animals and count them as family members, while simultaneously

consigning others, even of the same species, to experimentation.

He says that this is similar to caring about one’s immediate

family while ignoring the needs of strangers. Since biomedical research

is intended to benefit strangers, his comparison is strained. But Tannenbaum’s faith in the status quo, or the traditional

approach, is misplaced and, as mentioned above, rests firmly on

an ignorance of animals. This is especially ironic because Tannenbaum

is a veterinarian, though this might explain his odd recognition

of the interests of pets even as he discounts those of other animals

en masse. Tannenbaum says: Most animals in the wild spend most of their waking hours engaged

in the difficult tasks of obtaining food or avoiding predators.

It does not seem even remotely plausible to postulate that most

animals in the wild, or bred for use in research laboratories have

a need or drive to be happy or to lead a generally happy life in

the same way in which they have physiological needs to eat, drink

or eliminate. Many species of wild animals engage in play and other social interactions

such as mutual grooming. The traditional vision of “nature,

red in tooth and claw” was formulated long before scientists

had begun making detailed observations of animals living their lives

over time. It is now recognized that many animals have recurring

and significant amounts of leisure time and engage in activities

that appear to be pursued simply for fun. This is the case for river

otters, dolphins, parrots, many primates, dogs, cats, and rats,

to name only some of the more obvious examples. Tannenbaum’s

claim that “animals in the wild spend most of their waking

hours engaged in the difficult tasks of obtaining food or avoiding

predators” is simply false. That Tannenbaum’s “traditional approach” moral

theory is based on an ignorance of animals is further demonstrated

by his citation of work performed by his colleague at the University

of California, Davis, John Capitanio. Tannenbaum writes: One question that has received very little attention in the animal

research literature, but is becoming a concern for some scientists,

is how providing enjoyments and satisfactions to research animals

might affect the scientific results of important experiments. Primatologist

John Capitanio has found that the survival of monkeys infected with

simian immunodeficiency virus is significantly decreased when they

are exposed to social change (for example, by being moved into paired

housing with other monkeys) either after infection or in a ninety-day

period proceeding infection. Tannenbaum assumes, for the monkeys in question, that being moved

into paired-housing is an enjoyment or satisfaction. But it is well

recognized that pairing monkeys who have been isolated is problematic

and prone to difficulty. Injury due to aggression is common when

such pairing is done ad hoc. In such situations, enjoyment or satisfaction

do not appear to be the typical reaction of the monkeys. Capitanio

himself has been much interested in the effects of isolation rearing

in monkeys and has demonstrated a clear distain for their psychological

well-being. Tannenbaum’s citation of Capitanio’s “important”

experiments is simply an example of citing one person’s cruelty

as a justification for the cruelty of an entire industry. Tannenbaum wonders why people are beginning to change their opinions

about the importance of the experiences of animals being held and

experimented on. He is apparently unfamiliar with, or confused about,

current knowledge and literature regarding animals’ minds.

He seems locked in an archaic ethos and confused by the changes

he sees occurring around him. Tannenbaum’s ethical theories

are erroneous because they are based on confusion and ignorance. “Defending Animal Research: An International Perspective”

by Baruch A. Brody (pg 131-147). Baruch A. Brody’s essay is one of only two in the book (the

other is Frey’s) to present a thoughtful examination of the

ethics underlying the use of animals in research. This is likely

due to the fact that Brody is a professor of biomedical ethics. But moral theories can largely be placed into one of two categories:

prescriptions and apologies. Apologies attempt to justify some status

quo. Societal behaviors, or norms, develop over time, and often

do so in a relative absence of moral self-reflection. Societal norms

have emerged from traditions that are often rooted in ancient history,

and in some cases, such as the use of animals, in prehistory. Such

tradition-driven societal behaviors are unlikely to have been molded

and established through a self-reflective process. Moral theories

that present an ethical rationale for the status quo must always

be looked at with great caution and skepticism. The belief that society has luckily developed a particularly moral

behavior involving animals is counter to the historical record of

our behavior involving other people. But this is Brody’s

implicit claim and is why he presents an apology for the current

state of affairs rather than a prescription leading to a solution

to the problem of widespread, institutionalized, industrialized,

routine evil. In Brody’s defense though, he does admit that the U.S. regulatory

position is morally and rationally less defensible than many of

the regulatory practices in European nations. Brody classifies the

underlying moral beliefs that appear to be acting to formulate these

regulations as “lexical priority” – the U.S.

position, and “discounting” – the European position. Brody says that animals have interests, and that their interests

are morally relevant to the degree that the potential harm caused

to them must be acknowledged and weighed against the benefit to

humans that their use might provide. Brody acknowledges that, in

the U.S., in any weighing of interests, that animals’ interests,

no matter how great, will always lose to humans’ interests,

no matter how small. The European system, though weighing human

interests generally greater, does not allow a trumping of any human

interests over all animal interests. The European systems “discount”

animals’ interests, but do not zero them out. Brody believes

that the European system comes closer to being a “reasonable”

system, and that the U.S. system is extreme. As mentioned above, however, Brody does not seek to suggest a more

humane system than that already in place in some European countries.

He seeks merely to justify the general status quo and bemoans the

lack of a clear moral justification for animal experimentation within

the industry. Brody is particularly troubled by the lack of a rational

and moral principle or position explaining humans’ greater

significance. He says that this is the crucial question that must

be answered before any reasonable pro-research position can be adequately

expounded. The absence of this explanation, however, has been insufficient

for Brody to reverse his pro-vivisection position. To this degree,

like Morrison and Zola, Brody maintains his position through faith. Brody does raise an important point that bears further consideration.

He notes that the discounting of the interests of others is a human

society-wide morally accepted behavior. He notes that we discount

the interests of strangers when weighing them against the interests

of our family. Likewise, we discount the interests of other nations

when weighing them against our own nation’s interests. To

Brody, this explains why we can morally discount the interests of

animals – they are not humans, they are others. Brody points out that there are limits to these priorities, and

that cases could be imagined wherein the interests of strangers

might actually carry more weight than our own interests. To the

degree, however, that we generally do give greater weight to the

interests of our self, immediate family, kin, or nation, Brody asks

what the difference is between such priority and other discriminations

such as racism, sexism, or, in the case of other species, speciesism. Brody says that further philosophical study and thought is needed

to clarify this controversy. Hopefully, if human minorities were

being subjected to experimentation, Brody would speak out and perhaps

otherwise protest against such bigotry. The fact that he does not

do so now, having admitted that he cannot easily differentiate between

speciesism and other forms of immoral discrimination, makes his

position extremely weak and his conclusions and support of animal

experimentation suspect. Baruch A. Brody is the Leon Jaworski Professor of Biomedical Ethics

and the Director of the Center of Medical Ethics and Health Policy

at the Baylor College of Medicine and Professor of Philosophy at

Rice University. Readers could assume that when he speaks and writes

regarding the opinions and positions of other philosophers that

he would be accurate. But consider this comment: "…we have an obligation to human beings, as part of

our special obligations to members of our species, to discount animal

interests in comparison to human interests by testing new drugs

on animals first. From this passage, a reader must infer that Mary Midgley supports

animal research. On this point Brody is wrong to a degree that would

embarrass even an aspiring scholar. One of Brody’s anti-animal

allies, Daniel C. Dennett, comes much closer to accurately portraying

Midgley’s position when he says: "I am not known for my spirited defenses of René Descartes,

but I find I have to sympathize with an honest scientist who was

apparently the first victim of the wild misrepresentations of the

lunatic fringe of the animal rights movement. Animal rights activists

such as Peter Singer and Mary Midgley have recently helped spread

the myth that Descartes was a callous vivisector, completely indifferent

to animal suffering because of his view that animals (unlike people)

were mere automata." (“Animal Consciousness: What Matters

and Why,” in D. Dennett, Brainchildren, Essays on Designing

Minds, MIT Press and Penguin, 1998.) Midgley is the author of sixteen books and innumerable essays and

articles. She is among the most respected of contemporary philosophers.

The odd and radically disjoint claims concerning her position made

by the anti-animalists are indicative of their struggle to grasp

the reality of other animals as intrinsically important beings.

Baruch A. Brody’s comment concerning Midgley is far off the

mark. Brody’s citation for Midgley is her Animals and

Why They Matter. I was unfamiliar with this particular Midgley

work, so took the opportunity to read it upon being told by Brody

that I had misunderstood Midgley’s position. For that, I

owe Brody a debt of gratitude; Midgley’s argument for the

need to reassess our traditional view of animals is razor sharp.

Claiming that Midgley supports vivisection, based on the position

presented in Animals and Why They Matter would be just cause

to fail an introductory philosophy class. This point, as his reluctance

to apply the results of his own reasoning to the matter of harming

animals in experimentation, suggests, again, that Brody’s

analysis and position is woefully misinformed or contrived. Brody’s clear misrepresentation of Midgley suggests that

the editors were less than thoughtful as they put this collection

of essays together. Apparently, the criterion was simply that a

writer proclaimed that harming animals is just and reasonable. This

intellectual laziness by the editors, or perhaps bald-faced prejudice,

is evident throughout the text. “A Darwinian View of the Issues Associated with the Use

of Animals in Biomedical Research” by Charles S. Nicoll and

Sharon M. Russell (pg 149-173.) Charles Nicoll and Sharon Russell are cofounders of the Coalition

For Animals and Animal Research (CFAAR), which they claim is a nonprofit

educational organization. On the single-page website, http://www.swaebr.org/CFAAR/,

CFAAR says that the organization’s two goals are (1) “To

educate the public about the true nature of animal research and

animal researchers,” and (2) “To support the responsible

and humane use of animals in biomedical research.” This is confusing. In the cofounders’ current essay, they

write that, “moral theorizing about human duties to animals

is a pointless enterprise.” Exactly why treating animals

humanely is not a moral duty to them is not addressed. Nicoll and

Russell claim that their belief is founded on Darwinian evolution.

They say: “The relationships that develop between or among

different species (e.g. symbiotic or parasitic) are a result of

evolution. Since these relationships are based in biology, it is

nonsensical to moralize about them and to advance ‘rights’

for animals or even equality among species.” To the degree that Nicoll and Russell attempt to present a moral

theory about the human use of animals it boils down to the claim

that if any other species acts in ways that seem less than compassionate

or even cruel, then it is natural that we do so as well. The authors

attempt to root this claim in Darwinian evolution, claiming that

the exploitation of other species is natural, and therefore right.

This is the same justification used by a little boy caught doing

something wrong: Johnny did it. Nicoll’s and Russell’s confusion is likely due to

their unholy marriage of Darwin, who they seem to misunderstand,

and two of the leading anti-animal philosophers, Carl Cohen and

Peter Carruthers. Perhaps the authors’ deference to Cohen

and Carruthers is understandable since the authors are not themselves

philosophers and Cohen and Caruthers are among the few modern philosophers

and ethicists willing to discount the interests of animals willy-nilly.

But the authors are biologists, and their confusion about Darwinian

evolution has the ring of self-interest to it. Consider the quote

from above. They are correct that symbiotic and parasitic relationships are

a result of evolution and based in biology, but so what? Everything

we do is a result of our biology. We can read these words because

our brain has learned their meaning. Nothing we do is divorced from

our biology. What this means is that our decisions – arising

from the organic processes of our brains – on how we should

treat those different or weaker than ourselves, say, persons of

different ethnicity or children or people with physical impairments,

are based in our biology. It is absurd, and obviously so, to suggest

that these matters do not warrant “moralizing.” Likewise,

human relationships with other species can and do warrant moral

consideration. The authors’ claim to the contrary is simple

self-interest and self-defense speaking in place of rationality. This warped perspective is evident throughout the essay and should

be an embarrassment to university professors professing to be biologists.

Nicoll currently vivisects animals and teaches others to vivisect

at the University of California, Berkeley, and Russell did as well

for a number of years. Neither are ethologists however, so maybe

this is why they are so confused about animal behavior. Unfortunately,

their confused notions of animals, coupled with Cohen’s and

Caruthers’ own confused notions of animal behavior, form

the foundation for a philosophical position that is little more

than a failed search for a justification of the widespread, institutionalized,

industrialized, routine evil that the authors have contributed to

in their own laboratories. One of Nicoll’s and Russell’s claims is that there

is a propensity toward childlessness among animal rights activists.

They base this on a survey of activists who were in Washington D.C.

on June 10, 1990 for the “March for the Animals.”

Whether or not the demographic represented by the people with the

resources to travel to Washington for the occasion is typical of

those who are concerned about cruelty toward animals remains to

be seen, but 80% were reported to have had no children. The authors

suggest that this is because activists have little fondness for

children and that this lack of fondness is maladaptive in a Darwinian

sense. The claim of maladaption is surprising in light of our burgeoning

human population. To the authors, apparently, six billion people

consuming the planet’s resources at an ever increasing rate

seems a good strategy for our long-term survival as a species. Frankly,

the authors’ naked hatred of animal rights activists has

clouded their limited ability to think. It is hard to find a page of their essay on which their claims

do not collapse due to faulty thinking or a misstatement of fact

(Such as their claim that 25 million animals are used in biomedical

laboratories annually in the U.S. This is the industry’s

current estimate for the number of mice and rats alone.) The authors’

weaving of Caruthers and Cohen with their erroneous understanding

of animal behavior results in a confused view of nature. They write: "As applied by Carruthers, contractualism refers to entering

into a moral understanding with another being in which both parties

agree not to harm each other or other members of their kind. In

effect then they agree to abide by moral behavior that would be

in accord with the ‘Golden Rule.’ Only rational beings

(i.e., those with the capacity to reason) who have an understanding

of the concepts of morals and rights could enter into such a contractual

agreement. …we [can]not establish such an agreement with

any nonhuman species on our planet, even those that are the most

intelligent." Contractualism has been challenged by modern philosophers for being

too contrived. But from a behavioral point of view it is at least

understandable why such a theory emerged. When we check out at the

grocery store, we do not push to the head of the line. We act as

if there was a contract in place to which we have all agreed to

abide. But to the degree that this is natural behavior (as opposed

to behavior motivated by the fear of going to jail for assault)

it is behavior that is common throughout many animal societies.

Quite simply, animals are not constantly fighting with each other.

Many act as if they have agreed to get along. And it is not just members of the same species that act as if they

have entered into this contract. Many mixed species groups graze

together, flock together, swim together, and socialize with each

other. Either these animals have some semblance of a concept of

moral behavior, or else, such a concept is not needed in order for

us to get along with each other. Nicoll and Russell must be nervous

when a dog walks into a room with them since they believe he or

she is unable to understand that they are not going to attack each

other. The authors claim that the development of weapons is what led to

our ‘contractualist’ behavior. But, as mentioned above,

many animals get along with each other. They claim that this “Golden

Rule” of behavior is almost universal in human culture, but

they fail to acknowledge the internecine tribal warfare seen in

many traditional settings or the larger worldwide conflicts, or

people imprisoned for assault, rape, or murder. To the degree that

we do get along with each other, this behavior appears to be much

older than our species. It is not a human invention. Nicoll and Russell make many errors. They state that 99.9 percent

of all the species that have existed are now extinct. (They make

this point to frighten readers into thinking that we must fight

tooth and nail to survive.) But as biologists they should know that

this is not simply because these species suddenly succumbed to some

attack. To some degree, they evolved into the species we see today.

Just as wooly mammoths are now extinct, ten million years ago there

were no American robins. Many species have died out during cataclysmic events. Profound

climate changes, meteor impacts, and massive volcanic events have

led to many episodes of mass extinctions. The authors acknowledge

this, and admit that there is little to nothing we can do about

it at the present time short of colonizing other planets. But they

claim that there are threats to the human species that we can fight

such as insect infestations and disease. But the claim that these

problems are responsible for past extinctions is far fetched and

based on nothing other than a wish to justify animal experimentation. The authors claim that advanced human behaviors like fire-making

and human language led to monogamy and extended childcare. But monogamy

is seen in other species as well such as geese and gibbons. Extended

childcare is seen in elephants and whales and gorillas, to name

but a few examples. The authors should know this. The authors struggle

unsuccessfully throughout their essay to paint us as saintly and

all other animal species as devilish. The claim that humans are

historically monogamous is, at best, speculative. Modern human societies

are certainly not uniformly monogamous as a visit to many parts

of Africa or Asia will disclose. This review is too brief to catalog the myriad errors and inconsistencies

within this essay, but one point cannot be passed by. The authors

frequently defer to their moral helmsmen Carruthers and Cohen. [Cohen

demonstrated conclusively in The Animal Rights Debate (C.

Cohen and T. Regan, 2001) that he is not in possession of the basic

facts regarding animal experimentation in the U.S.] Using him as

their guide to defending speciesism, the authors state: "Sexism and racism are not justifiable because normal men

and women of all racial and ethnic groups are, on average, intellectually

and morally equal, and their behavior can be judged against the

same moral standards. Animals do not have such equivalence with

humans. To deny rights or equal consideration on the basis of sex

or race is immoral because all normal humans, regardless of sex,

ethnicity, or race, can claim the rights and considerations that

they deserve, and they know what it means to be unjustly denied

them. No animals have these abilities. Speciesism…is a normal

kind of discrimination displayed by all social animals, but racism

and sexism are widely considered to be morally indefensible practices." This passage is a good example of the reasoning being employed

by Nicoll and Russell throughout their essay. First, we do not judge

only “normal” men and women as morally equal. Second,

the behavior of humans from different cultures cannot always be

judged against the same moral standards, so the authors’

premise is false. Third, if not all humans are judged against the

moral standards of “normal” men and women (whatever

that might mean), why should animals be so judged? Fourth, rights

are not dependent upon the ability to claim them. Children, many

elderly people, even the poor, are often unable to claim the right

of equal consideration, yet they are entitled to it. Why should

animals be held to a higher standard? Fifth, if one kicks a dog

for no apparent reason, the dog acts as if he or she has been wronged,

thus they behave as if they do know what it means to have a basic

right such as the “Golden Rule” unjustly denied to

them. Sixth, though speciesism may be “normal” today,

this makes it no less wrong than the “normal” discriminations

of the past. Seventh, not all social animals display speciesism

– as common instances of mixed species grazing, schooling,

flocking, and socializing clearly demonstrate. As mentioned above, and as this single passage so readily demonstrates,

the errors in the current essay are extensive and relentless. This

is the level of false justification required to defend the status

quo. “Animals: Their Right to Be Used” by H. Tristram

Engelhardt, Jr. (pg 175-195) H. Tristram Engelhardt, Jr. explains in his essay’s first

footnote that he is an Orthodox Christian and that his real moral

guidance concerning the human use of animals comes from the covenant

between God and Noah: "And God blessed Noah and his sons, and said unto them, Be

fruitful, and multiply, and replenish the earth. And the fear of

you and the dread of you shall be upon every beast of the earth,

and upon every fowl of the air, upon all that moveth upon the earth,

and upon all the fishes of the sea; into your hand are they delivered.

Every moving thing that liveth shall be meat for you; even as the

green herb have I given you all things." Engalhardt believes that every animal fears and dreads humans because

God has made it so. His essay is remarkable for its demonstration

of what can happen when a person with this foundational belief attempts

to build a moral theory concerning animal use, divorced from the

moral guidance of (even) a cruel deity. This moral freefall results

in an absurd and rudderless reveling in any and all uses of animals. In Engelhardt’s opinion, the most trivial of human interests

are more than adequate justification for any and all uses of animals.

This leads to his moral theory’s endorsement of such enjoyments

as watching animals kill each other in staged fights or animals

being tormented and killed slowly in public spectacles. Englehardt says that the “full moral significance of animals

can be understood only with reference to their contributions to

human contemplation, delight, amusement, welfare, and culture.”

This leads to his absurd claims that animals have the “right”

to be hunted, eaten, domesticated, bred, genetically modified, skinned,

harvested, to be used as beasts of burden, to be used in circuses,

bullfights, cockfights, rodeos, to be dissected, experimented on,

used to test cosmetics, and used in any other imaginable way. Englehardt is a member of the Center for Medical Ethics and Health

Policy at Baylor College of Medicine. He is a professor of philosophy

at Rice University. Can it be any wonder that an industry that is

responsible for widespread, institutionalized, industrialized, routine

evil has taken root with such leadership? With moral leaders such

as Englehardt deciding what can and cannot be allowed to occur in

U.S. laboratories, is there any limit to what could be allowed?

The evidence from the labs themselves demonstrates that there is

not. “Justifying Animal Experimentation: The Starting Point”

by R.G. Frey (pg 197-214)

It seems safe to assume that the editors gave some thought to the

placement of the essays within Why Animal Experimentation Matters:

The Use of Animals in Medical Research. R. G. Frey’s

essay is the final comment. Frey points out rightly that the common premise in every defense

of vivisection is the “argument from benefit.” This

is the simple recurring justification that animal experimentation

saves human lives. Frey, himself, accepts this as a premise for

his own position. He then notes that this justification cannot stand

on its own merits, but requires a clear explanation of why it would

be wrong to experiment on any humans but acceptable to experiment

on animals. To the degree that Frey writes as a reasonable man, he methodically

and convincingly dismantles the answers presented to this problem

by the volume’s preceding authors. This leads him to adopt

what he calls the “quality of life view.” This view

is rational and internally consistent. He notes that any attempt

to explain or define a criteria that can be used to differentiate

humans and other animals, with respect to a rational explanation

for why we can vivisect one but not the other, will lead to an overlap

between humans and animals. In other words, there will be humans

with such low quality lives – however defined – that we

will have to include them in our pool of experimental subjects.

Most vivisectionists will be alarmed by Frey’s clear and

compelling reasoning. But Frey’s support for animal experimentation is built on

a questionable foundation and weakened further by something akin

to simple bigotry. First, Frey writes: “If the use of animals

is scientific and medical research is justified, it seems reasonably

clear that it is justified by the benefits that this research confers

on humans.” Then: "The argument from benefit is a consequentialist argument:

it maintains that the consequences of engaging in animal research

provide clear benefits to humans that offset the costs to animals

involved in the research. This is an empirical argument and so could

be refuted by showing that the benefits to research are not all

that we take them to be. This is not the place to undertake an examination

of the costs and benefits of the myriad uses that we make of animals

in science and medicine, nor am I the person to undertake such an

examination." Apparently, if it could be shown that research using animals provided

less than a “clear benefit to humans,” much of Frey’s

subsequent argument would be false. Based on his faith, Frey makes the claim that: “It is ironic,

to say the least, that abolitionism has received so much attention

in the media of late at the very time that scientific and medical

research seems on the threshold of revolutionary discoveries that

will greatly alleviate human suffering.” He goes on to list

the discoveries that are just over the horizon: an AIDS breakthrough,

genetically engineered animal organs for transplant, and cloning.

It is obvious that someone who acknowledges that he is unsuited

to examine “the costs and benefits of the myriad uses that

we make of animals in science and medicine” is unlikely to

be able to predict whether current research using animals is likely

to lead to “revolutionary discoveries.” And where does Frey get his information on which to base his faith

that animal research is clearly beneficial to humans? He cites no

specific source; he says only that science and medicine wish us

to believe that there is benefit, and that the media tells us that

this research is what the public wants. This seems a weak justification

for an entire industry undeniably hurting animals on an almost unimaginable

scale. Frey frankly ignores the evidence that animal research is less

than clearly beneficial, and is frequently even harmful to human

health. There is now ample evidence to suggest that the benefits

on which Frey bases his thesis are suspect. If, as he claims, this

essay was not the place to make a cost benefit analysis of animal

research, he should have at least cited what literature is available

on which to make such a determination. If he has not reviewed this

literature, then his thesis is little more than an unreasoned faith-based

defense of cruelty. But Frey might indeed be willing to make claims in the absence

of evidence, as have done many bigots in the past. That Frey is

a bigot, slips through a few times in his essay, but no where more

clearly than in this statement: It should be obvious by now why the search for distinguishing characteristics

that are very strongly cognitive, such that their use would exclude

all animals from the class of protected beings, is doomed to failure.

If such criteria were identified, the number of humans who would

fall outside the protected class seems certain to increase, depending

upon how sophisticated a set of cognitive tasks one selects as the

screening characteristics. Making the cognitive task less sophisticated,

in order to protect as many humans as possible, creates the risk

that some animals will be included within the protected class, even

as some humans fall outside it. (My emphasis.) So, we have to assume that including any animals within the “protected

class” is simply unthinkable to Frey, no matter what moral

argument might be proffered to justify such a categorization. Frey

is more worried about placing any species of animal out of bounds

for experimentation than he is about including some humans within

such boundaries. Frey sums up his stance: "Some will conclude that my position vis-à-vis impaired

humans is so objectionable that my argument is tantamount to a rejection

of animal experimentation. I don’t see it that way. For me,

the crucial question is: will we decide to forego the benefits that

scientific and medical research promise? It is hard to imagine that

we will. Hence, we are faced with the problem over humans." Sadly, Frey has completely missed the fact that medical breakthroughs

and progress have been the result of human-based research and investigation.

This leads him into an alley with only two exits: experiments on

animals or no research at all. His solution appears to be based

on a profound, and perhaps willful ignorance of medical history. Frey’s theory remains problematic, however. Even if he finally

realizes that the benefits he imagines arising from animal experimentation

are an always distant glimmer, like a mirage of cool water beckoning

on the horizon, he will still be left with the unassailable logic

that, to the degree that we have to sacrifice someone – now

humans – that it must be those with a lower quality of life.

One thing is certain: Frey will always draw the line so that he

is among the protected class. In Summary…. The essays in Why Animal Experimentation Matters: The Use of

Animals in Medical Research have uniformly failed to answer

the problem presented by vivisection, an industry that is responsible

for widespread, institutionalized, industrialized, routine evil.

A few of the essays are worth reading, nevertheless. First and foremost, we are given some insight into the minds of

the vivisectors. Adrian R. Morrison, Stuart Zola-Morgan, Charles

S. Nicoll, and Sharon M. Russell have all spent years systematically

hurting animals. Their attempted justifications (or lack thereof)

make this volume worthwhile reading. The essays by Baruch A. Brody and R.G. Frey give us a good idea

of the current effort to defend vivisection philosophically. These

essays demonstrate that solid resilient arguments have yet to be

presented. The two remaining essays, by Jerrold Tannenbaum and H. Tristram

Engelhardt, Jr., are so outlandish and mean that one wonders whether

the editors included them in an effort to shift the center further

toward the cruelty end of some spectrum. They are intellectually

suspect and written by apologists with little real understanding

of the issue; they can be dismissed as filler. Rick Bogle. September, 2002

Home Page | Our Mission | News |