|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

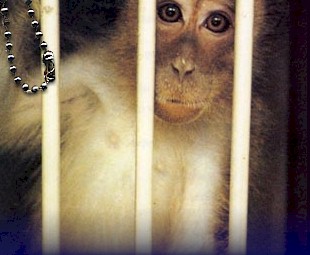

[The following is a verbatim copy of an official University of California Los Angeles document involving one of the many primates killed by the university.] Animal Medical Report May 12, 2000

Vervet monkey I.D. #9382 On May 10, 2000, animal #9382 was scheduled to be used in a study at UCLA. This study required transferring the animal consciously from its vivarium cage, in room [deleted] to a primate transport cage. The transfer procedure involves securing a primate transport cage at the entrance of the vivarium cage. Next, the vivarium cage squeeze mechanism is engaged in order to position the animal and direct it into the transfer cage. This transfer procedure was developed and approved by the [deleted] as the primary means for transferring a conscious male Vervet monkey into a transport cage. This procedure has been used successfully for several years at [deleted]. Subsequently, this procedure has been adopted by the UCLA Primate Research personnel and the UCLA Division of Laboratory Animal Medicine. It has been in use here at UCLA successfully for several years without incident. While transferring animal #9382 from its vivarium cage to the transport cage, the animal began biting the metal vivarium cage. Biting has been observed previously with other Vervet monkeys. After the animal was secured in the transport cage, it was observed that the animal was bleeding from its mouth and was having difficulty opening and closing its mouth. Initially it was believed that the animal had either bitten its tongue or broken a tooth from biting the cage. The animal was then anesthetized and examined by UCLA Veterinarians. It was concluded that the animal had a fractured maxilla. This was very surprising as we did not notice any particular action that resulted in this condition. Furthermore, this was a standard procedure that had been used for several years without any injury to any animal. We suspect that the animal’s head was either struck by the metal vivarium cage door as he entered the transport cage, or, that he banged his head against the side of the metal vivarium cage before entry into the transport cage. Upon recommendation of the attending UCLA veterinarians, the animal was euthanized and perfused. Its brain was removed for tissue analysis. This animal brain has been added to our control subject cohort for studies on basal ganglia function in non-human primates. We have altered our transfer procedure to ensure that this outcome will never occur again. Specifically, if the animal shows any resistance during the transfer procedure, it will be administered a low dose of the anesthetic Ketamine, and then safely transferred into the transport cage. The animal will then be monitored in the procedure location until it has fully recovered from the anesthesia and before participating in any conscious study. The medical report above, in spite of its claims to the contrary, suggests that the primates used by UCLA are subject to rough treatment, which we believe is a common occurance at such facilities. Daily exposure to suffering has been repeatedly shown to desensitize those exposed regularly to it. The document was part of a partial response by the University of California Los Angeles (UCLA) to an open records request filed by a UCLA honors student seeking information on the use of primates by her university. A small portion of the information she requested at the beginning of the 2002 school year was released months later only after repeated requests, much determination, and public protest. The university has not released a census of the primates at the university. This report has brought to light a facility hitherto overlooked by us. The name of the facility seems to vary depending upon the source of the information. It is referred to variously as: the Vervet Research Center, the Sepulveda Valley Nonhuman Primate Research Facility, the UCLA-VA Vervet Monkey Research Colony (VMRC), or simply, the Sepulveda Primate Facility. It is located next to, and administratively associated with, the Veterans Administration Hospital in Sepulveda, California. Documents from UCLA suggest that there are at least 500, and perhaps more than 700, vervets held there. Infant mortality is said to be high, but is offset by the larger number of births. The population is increasing.

The medical record above was included among documents associated with UCLA researcher William P. Melega, PhD. UCLA received $341,097 in FY 01/02 from the NIH National Institute on Drug Abuse (NIDA) to support Mr. Melega's research. The funded project was begun in 1997 and is marked for funding through March 2005. At the end of the period, his research will have generated over $1.5 million for UCLA. Mr. Melega studies the long-term effects of methamphetamine injections in vervets.

To the best of our knowledge, Mr. Melega is the only scientist in the world who has, or is, using vervets in methamphetamine experiments. This single point exposes the myth that a particular animal species is chosen as an experimental model for any reason other than accessibility. Further, it mocks a foundation of scientific investigation, reproducibility, since vervets are uncommon in primate labs. More disturbing is the fact that experiments underway across the nation are studying the effects of methamphetamine on the brains of human methamphetamine users. This makes the information gained by Mr. Melega even less valuable. #9382, rest in peace.

Home Page | Our Mission | News |

|||||||||||||||||